Astronomers confounded by a mysterious million solar-mass dark object whose inner structure defies explanation

An international team of astronomers have uncovered what may be a new type of unseen dark object in the distant Universe that doesn’t seem to resemble anything observed before. The object, which has a mass of about one million times that of our Sun, was previously discovered through the subtle gravitational distortions it imprints on the images of a strongly lensed radio jet. From a new analysis, published today in the journal Nature Astronomy, the team have now tested various models for how the mass is structured within the enigmatic object to uncover what it could be. To their surprise, the data rule out all conventional explanations, but instead point towards an extremely compact object, like a black hole or a dense stellar nucleus, that is embedded in an extended disk of matter that, so far, also doesn’t seem to emit any detectable light.

Uncovering the invisible

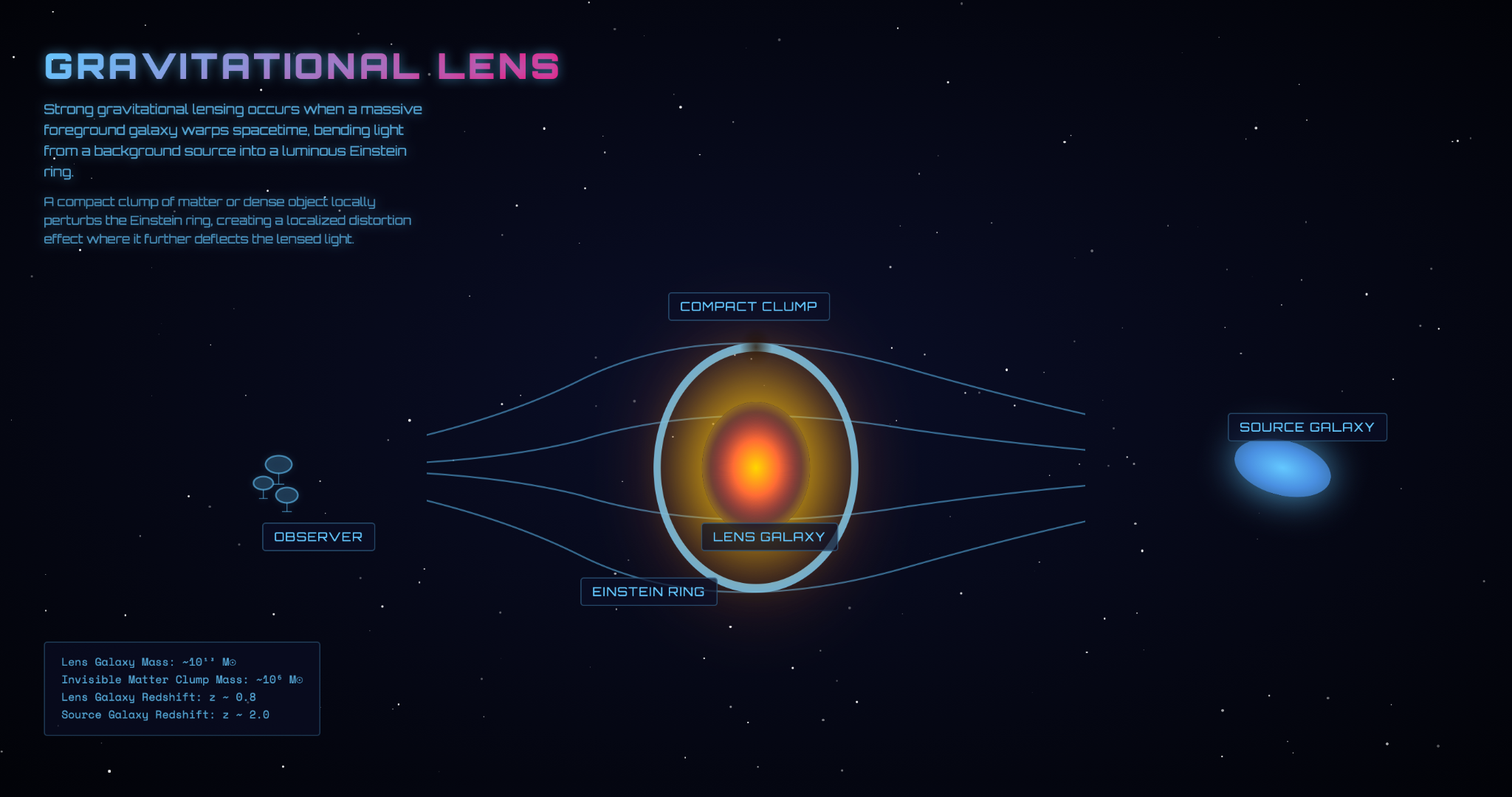

Astronomers have long relied on a phenomenon known as strong gravitational lensing—the bending and magnifying of light by massive objects—to probe invisible structures in the Universe. In many cases, these distortions act as natural cosmic microscopes, revealing otherwise undetectable concentrations of dark matter, the elusive substance that is thought to make up most of the mass in our Universe. By analyzing the way background light is warped, scientists can map the mass of intervening objects with extraordinary precision, even when those objects emit no light of their own.

For their analysis, the team combined radio telescopes from around the world, including the Green Bank Telescope (GBT), the Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) and the European Very Long Baseline Interferometry Network (EVN). The data from this international network of radio telescopes were correlated at the Joint Institute for VLBI ERIC (JIVE) in the Netherlands, forming an Earth-sized super-telescope that captured the precise details of the tiny gravitational lensing distortions caused by the thus far invisible low mass object.

Dr. Simona Vegetti, lead author of the paper published today in Nature Astronomy, explained how difficult the modeling analysis was, “Trying to separate all of the different mass components of such a distant and low mass object with gravitational lensing was both extraordinarily challenging and incredibly exciting. We’re working with high data quality and complex models, and just when I thought we’d pinned it down, its properties threw us another curveball. That combination of difficulty and mystery is exactly what makes this object so compelling.”

By combining the high fidelity of the lensing data with sophisticated analysis tools, and a massive amount of computing power, Dr. Vegetti and her team were able to characterise the structure of the low mass object over a range of radii with unprecedented detail. Vegetti continued, “The central inner part is strikingly compact, consistent with either a black hole or a dense stellar nucleus that surprisingly makes up about a quarter of the total mass of the object. As we go out from the centre, however, the density of the object flattens into a broad, disk-like component. This is a structure that we really haven’t seen before, and so, it may be a new class of dark object”.

A possible problem for dark matter theories

In terms of its overall size, structure and mass, the object could fall within the family of ultra-compact dwarf galaxies with some extended stellar halo of stars. These are rare systems that bridge the gap between massive star clusters and small galaxies, but the team have yet to detect the light from any stars embedded within the object. Even for this category of compact galaxies, the measured internal structure of the object remains highly unusual. If it were instead purely dominated by dark matter, its strange structure would be inconsistent with astronomers’ expectations for what such dark objects should look like.

Prof. Simon White, a co-author of the study said, “Our standard view of how cosmic structure forms predicts that there should be many starless dark matter lumps with mass a million times that of the Sun, but it predicts a structure for them which is very different, in particular much less centrally concentrated than what we have found here.”

Although the observed properties of the object deviate dramatically from the predictions of the standard cold dark matter model, which underpins much of our understanding of the Universe, one speculative alternative is that the dark matter is self-interacting. In such a scenario, the object could be a dark-matter halo whose centre has collapsed to form a black hole. However, additional numerical modelling will be required to test whether such a theory can replicate the observed density profile of the object.

This is the third such object to be identified using the so-called gravitational imaging method, but is by far the smallest in terms of mass and the first to be characterised to such a precise level. All three detections exhibit properties that sit uneasily within the standard dark matter framework. Identifying more examples will be crucial for determining whether these systems are rare outliers or are the first hints of physics beyond the current dark matter model.

Co-author Prof. John McKean added: “We’re hopeful that this detection is just the first of many to be studied in such amazing detail with high-resolution radio telescopes. With ongoing wide-sky surveys and the ever-improving power of high–angular-resolution follow-up observations, we should soon be able to uncover a whole population of these elusive low-mass systems, which will definitely teach us something new about our Universe.”

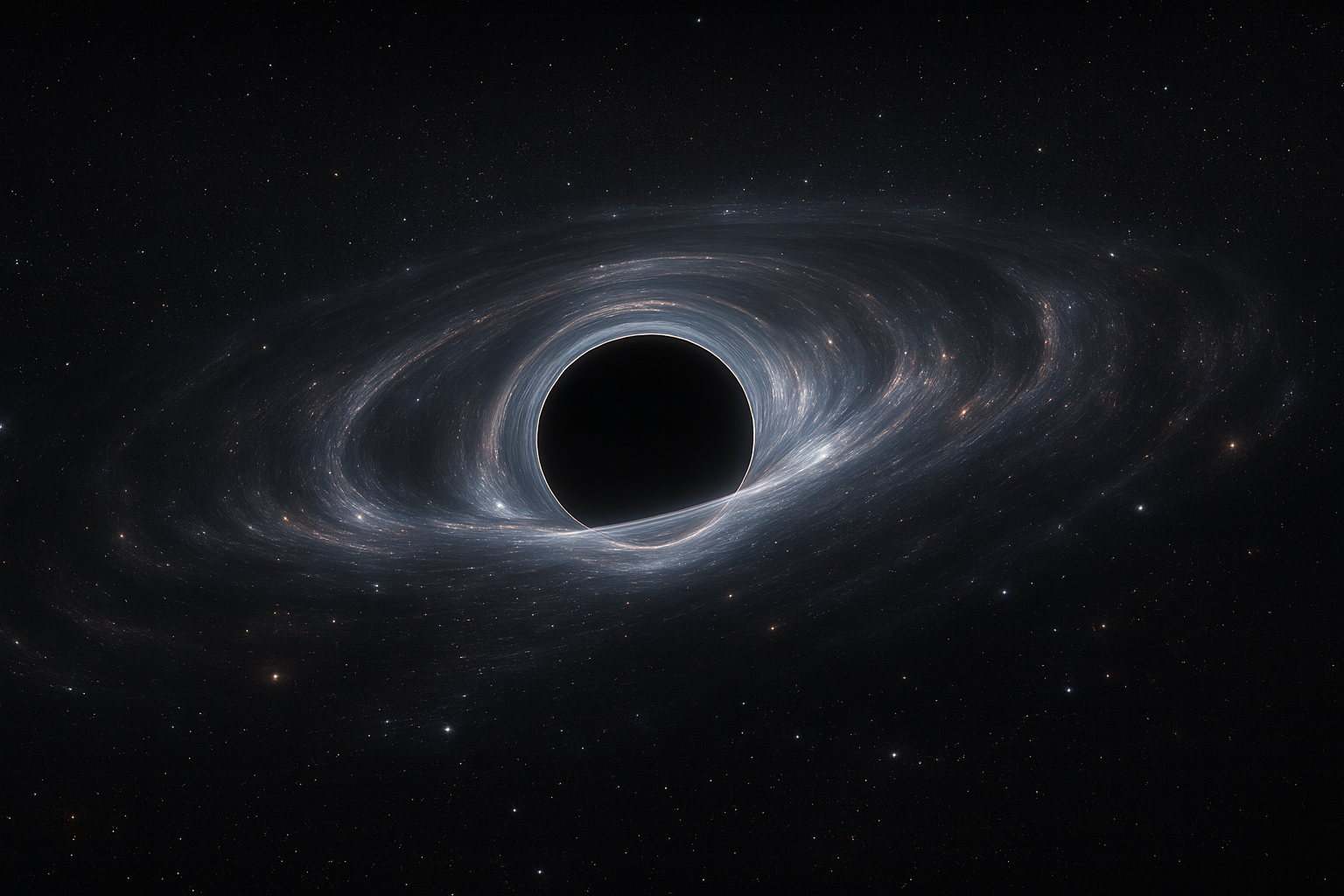

Figure 1: Representation of a possible scenario for the object, which includes a black hole that has a mass of about 300,000 times that of our Sun and an extended dark disk, which can only be characterised through their combined gravitational lensing effect on the distant Universe.

Figure 2: Schematic view of the gravitational lens system.

Additional information

Gravitational lensing: This is an astrophysical tool used by astronomers to measure the mass properties of structures in the Universe. It is a consequence of Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, where mass in the Universe curves space. If the mass of the foreground lensing object (typically a galaxy or cluster of galaxies) is sufficiently dense, then the light from distant objects is distorted and multiple images are even seen.

Very Long Baseline Interferometry: The radio observations were taken using a combination of radio telescopes that are combined to form a so-called Very Long Baseline Interferometer. This observational method allows astronomers to improve the imaging sharpness of the data and reveal very small fluctuations in the brightness that otherwise could not be seen. The telescopes included in the observations used in this analysis were the Green Bank Telescope and the Very Long Baseline Array of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in the United States, and the telescopes of the European Very Long Baseline Interferometric Network.

Paper link

Vegetti et al. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-025-02746-w

Additional Paper links

Powell et al. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-025-02651-2

McKean et al. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnrasl/slaf039

Contacts

Dr. Simona Vegetti, Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics: svegetti@mpa-garching.mpg.de

Prof. Simon White, Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics: swhite@mpa-garching.mpg.de

Prof. John McKean, University of Groningen, University of Pretoria, and South African Radio Astronomy Observatory: john.mckean@up.ac.za

About JIVE and the EVN

The Joint Institute for VLBI ERIC (JIVE) has as its primary mission to operate and develop the European VLBI Network data processor, a powerful supercomputer that combines the signals from radio telescopes located across the planet. Founded in 1993, JIVE is since 2015 a European Research Infrastructure Consortium (ERIC) with seven member countries: France, Italy, Latvia, the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Spain and Sweden; additional support is received from partner institutes in China, Germany and South Africa. JIVE is hosted at the offices of the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON) in the Netherlands.

The European VLBI Network (EVN) is an interferometric array of radio telescopes spread throughout Europe, Asia, and South Africa that conducts unique, high-resolution, radio astronomical observations of cosmic radio sources. Established in 1980, the EVN has grown into the most sensitive VLBI array in the world, including over 20 individual telescopes, among them some of the world's largest and most sensitive radio telescopes. The EVN is composed of 13 Full Member Institutes and 5 Associated Member Institutes.

Additional information on NanShan 26-meter Radio Telescope (NSRT, Ur)

The VLBI operation team at the Nanshan Station (Ürümqi) of Xinjiang Astronomical Observatory, Chinese Academy of Sciences, operated the NanShan 26-meter Radio Telescope (NSRT) to participate in this campaign organized by the European VLBI Network (EVN).

The NSRT (Ur) was built in 1991 with a 25-m aperture. In 2014-2015, the telescope was fully upgraded and re-commissioned. The NSRT is located in the hinterland of Eurasia. Its unique location and advanced VLBI system make it play an irreplaceable role in the EVN and the East Asian VLBI Network (EAVN) . As a core member of the Chinese VLBI Network (CVN), NSRT also participated in the accurate orbit determinations of the Chang’e lunar missions and the Mars exploration program.

Attachment Download: